Letter

“When I use a word,” Humpty Dumpty said in a rather scornful tone, “it means just what I choose it to mean – neither more nor less.” “the question is,” said Alice, “whether you can make words mean so many different things.” “The question is,” said Humpty Dumpty, “which is to be master – that‘s all.”1

Language as an entity — by Maik Schlüter

Language is a construct and a tool of communication, based on a complex and complicated set of rules. And while it never represents an entity itself, but solely implicates something, language claims a descriptive power over everything. Who possesses interpretational sovereignty over words? Mankind is “wording” the world and assigns descriptions and terminology to its multitude of phenomena, entities, and parts. The secret to language is its ambiguity: it is a system of distinguishable phonemes as well as a systematic array of characters. The use of chiseled sentences and binding grammatical rules may be an anthropological idiosyncrasy. Only man is able to marry language and mind so perfectly. Unlike animals, man can always refer to something beyond himself. But how does language develop? Is it an organism that grows, evolves and changes to eventually age and decay? Or is language a cohesive and preestablished system that has to be acquired in compliance with its grammatical, syntactical and semantic rules? An entity taking shape within ourselves, a room one is thrown into, exposed to its relentless diktat of sound, meaning and structure? Or is language a virus from outer space, like William S. Burroughs once claimed? What happens if we do not learn a language correctly, if we deny the validity of its paradigms and systematics, or develop aphasia? We then no longer fit into the system of messaging and receiving, of encoding, explaining, interpreting and evaluating. Questions arise: Who is more powerful, what is allowed to be said and to which effect in terms of meaning.

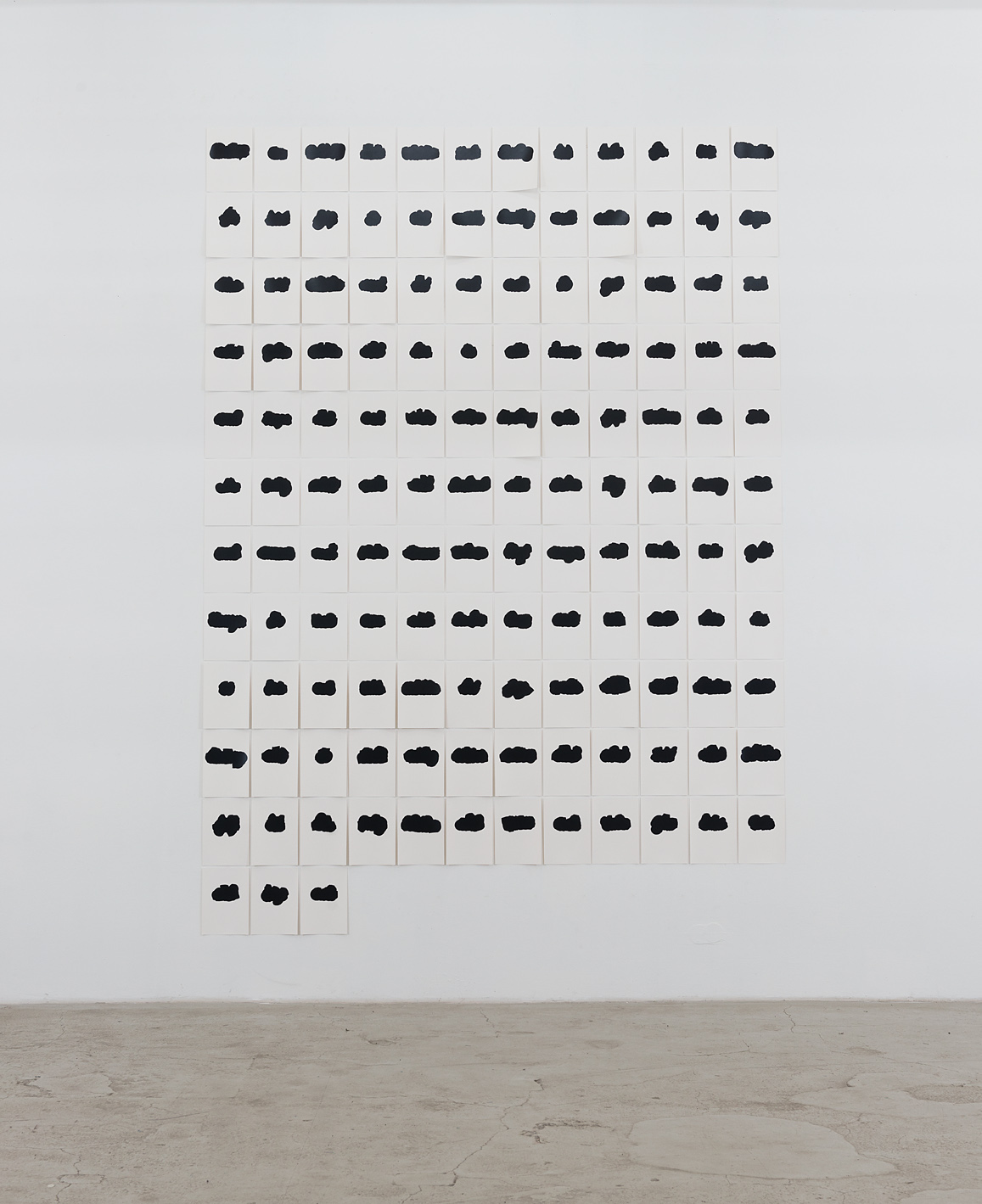

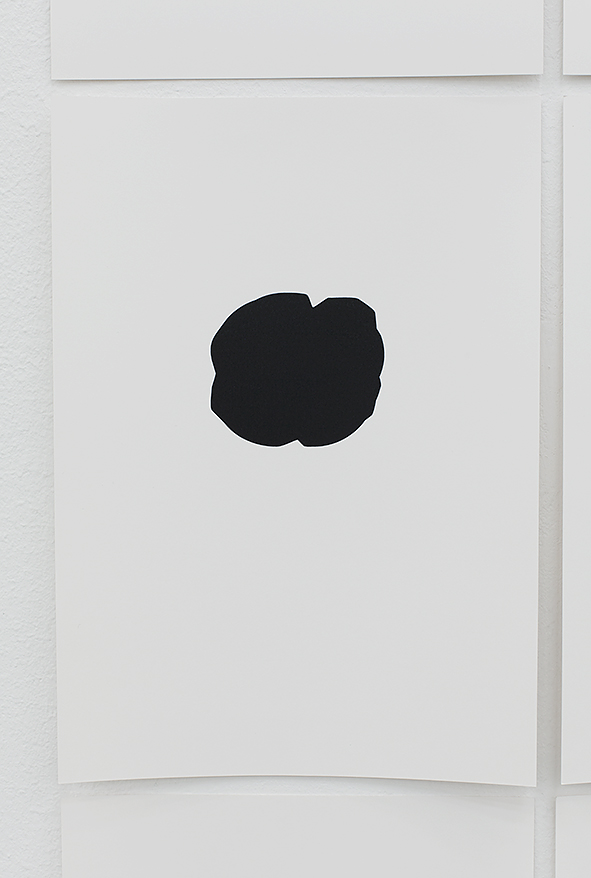

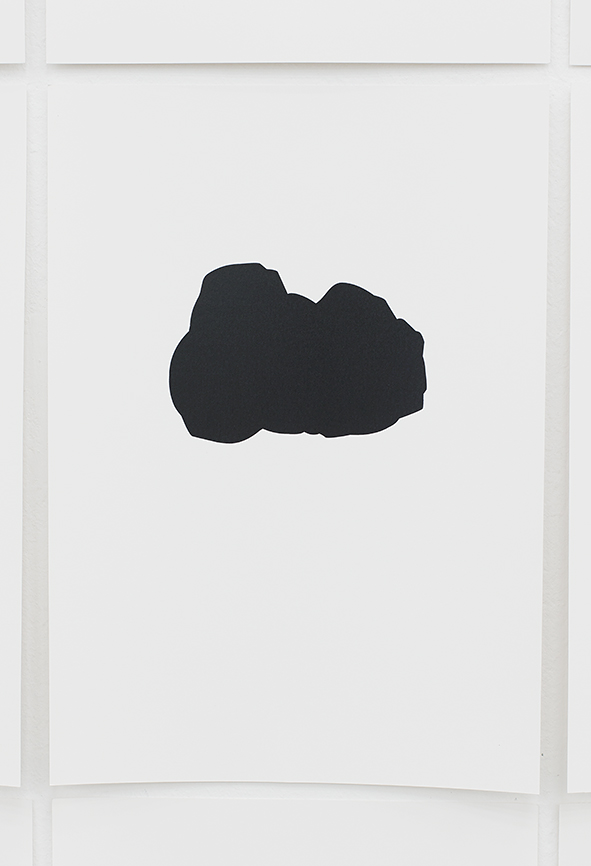

One of the works of Anna Vovan is ambiguously entitled “Letter” (2015), which refers to both the single character and the written message. The work consists of 135 A4 sheets of paper, on which neither letters nor words are recognizable. Black abstract and amorphous shapes are placed on the upper third of the page; sometimes reminiscent of black sausage links, or the outline of a speech bubble or graffiti. But one may also compare the depicted forms to the blackening that occurs in censored texts or text fragments. The table-like array gives the presentation a systematic austerity and orderliness similar to the logics of a phonetic alphabet.

All efforts to recognize script or a legible text fail. “Letter” offers neither words nor sentences, no onomatopoeic signs or any other form of paradigmatic semiotics. The black forms behave like a blind spot in the logics of speech and writing. Yet they are explicitly based on script and contain an entire letter. Anna Vovan has enlarged the words of one of her grandfather‘s hand-written records to such a gigantic extent, that due to a lack of structural and relational coherence they become illegible. What has been said and with what intention? Who is supposed to be the recipient? What happens if one reads a letter not intended for one to read? What conclusions and feelings arise from reading the message? At what point in time is the record located? Does one project the content into the future, link it to the present or try to reconstruct something that is history already? While viewing the work of Anna Vovan we receive no answers to these questions but are excluded from the systemic parameters of a certain undefined message. Here script constitutes an abstract image and narration gets visually segmented.

On this level, “Letter” expresses a profound distrust in language. Perhaps the letter was illegible in to begin with, or insufficient in terms of a meaningful statement? On the other hand the content may have been so moving or shocking that it had to be distorted and visually interpreted? In Anna Vovan‘s work script and language are being contradicted within their own framework, with language itself as the starting point. The artist does not paint over in terms of blackening, rather the visualization manifests itself as a probe into the wording process. An advance into the physical existence of meaning. Language becomes an undefinable, elusive entity in the work of Anna Vovan.

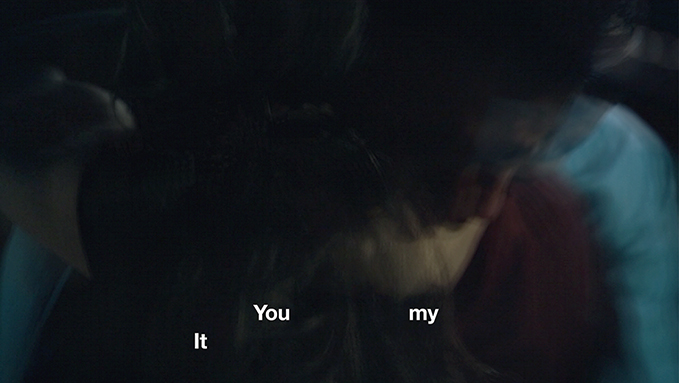

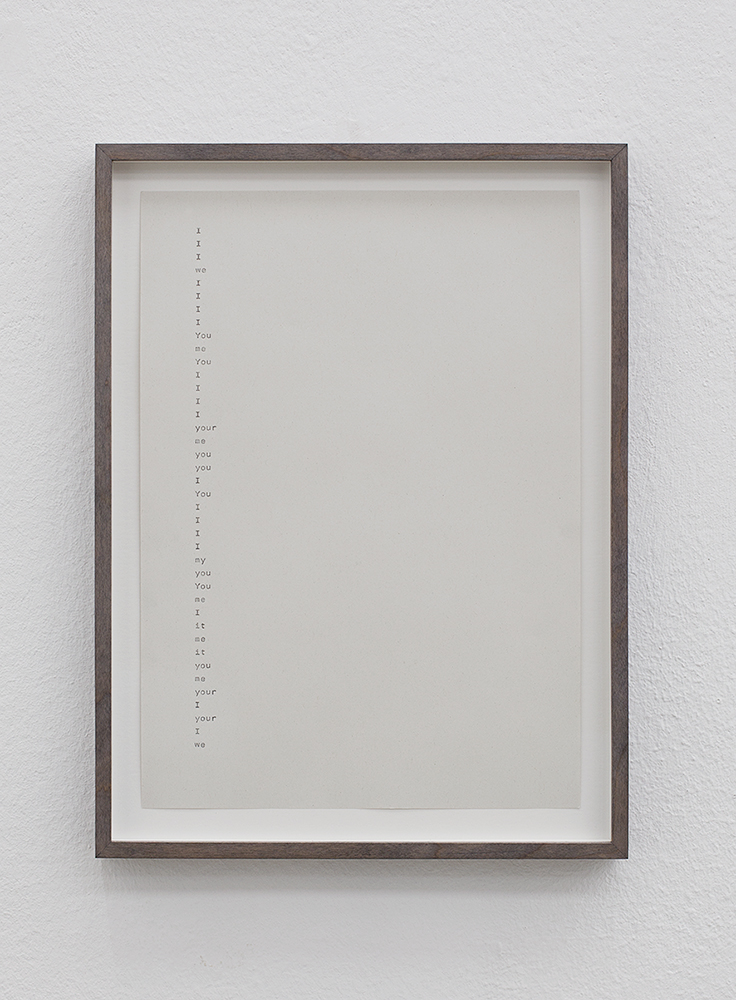

In “V. Woolf (28.03.1941)” (2015), the boundaries of language are exposed along with the helplessness and despair caused by the loss of verbal means of expression. Virginia Woolf‘s farewell letter, written to her husband shortly before her suicide, is a touching document of fear, of loneliness, of ailment and the realization of having nothing left to say. Anna Vovan reduces the already brief statements to only personal pronouns. In-between seemingly lies a world, which is only coherent, when mirrored in a personal relationship. No matter whether real experience, sensuality, love or forms of imagination are concerned (boundaries, in fact, vary), the speechlessness caused by depression and mania results in an existential loss of the bond to a loved individual and the world.

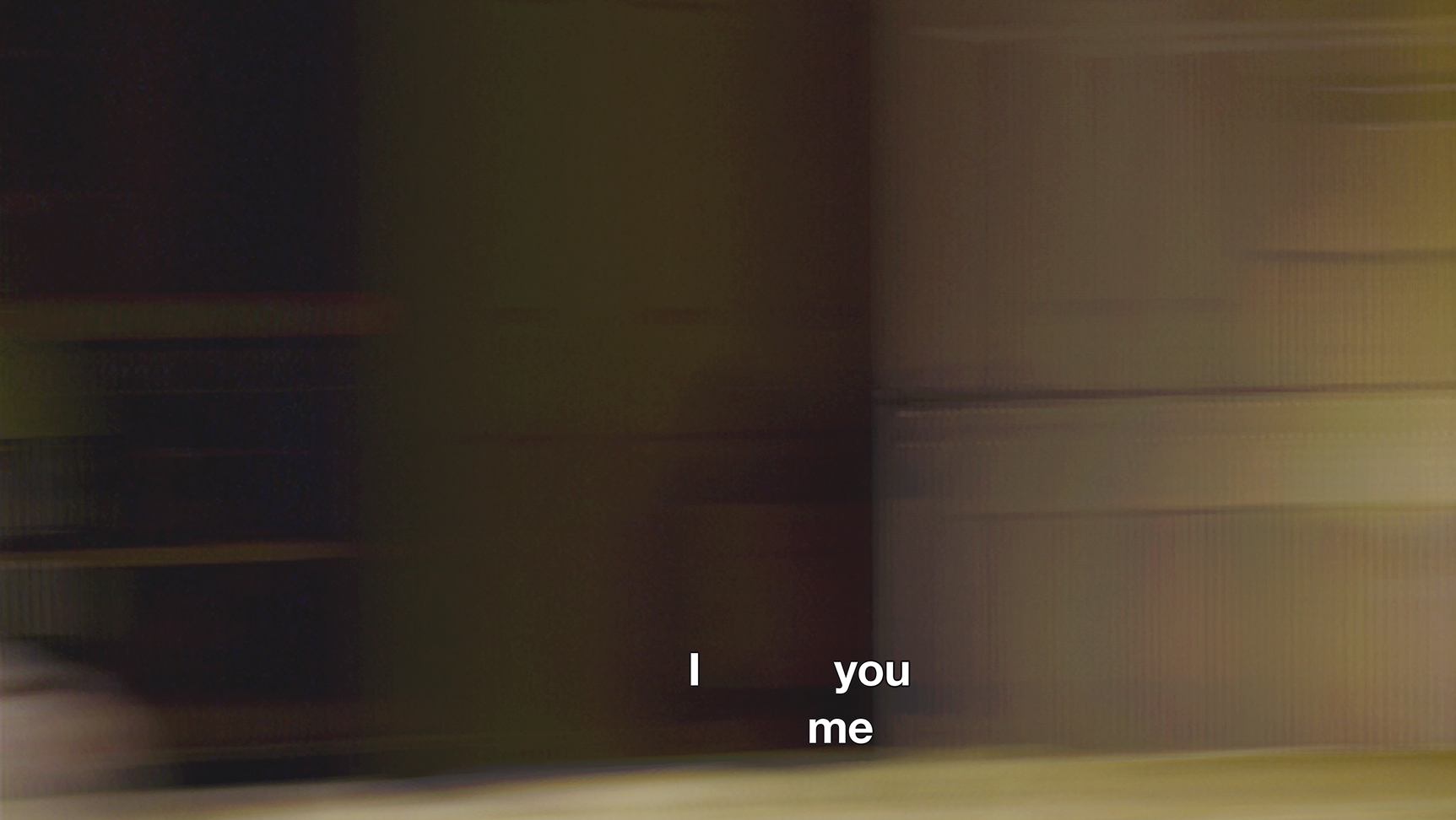

The same relation can also be found in the movie stills titled “It we”, “I you me” or “I her” (2015). Here not by an authentic profession like the one by poet Virgina Woolf, but more so by a never-ending stream of images, words and narratives incessantly produced by the film industry. Anna Vovan generates stills from film sequences and sandwiches them. Her choice, however, is not guided by images but by the displayed subtitles, which enable a legibility of words and actions synchronous with the spoken word. Here too, Vovan‘s interest solely centers on the personal pronouns. Every sentence and every dialogue is reduced to aspects of affiliation, reception, address or attribution by this approach. How many movies are there thematically centering on “you” and “I”? Are there any other topics anyway? And what is it all about? Love, hate, jealousy, fear, sex, power, lies, deceit, luck, submission? The film is devoid of narration. An existential reduction to human verbal interaction remains. But within the finiteness of topics and words lies an infinity of meaning and combinatorics, even when the content remains the same.

The absence of words can be seen in the work “Gap” (2015). But is that true? Can absence actually be seen? And isn‘t “Gap” much more about hearing? It is common knowledge that sound can not be seen, but beyond visibility words, sound and noise are always perceivable. Oftentimes one is forced to hear things one does not want to hear. On the other hand one may apply his or her sense of hearing to something not supposed to be heard. Speaking and being heard are axiomatically intertwined. Words without a recipient or failing to be heard lead into isolation and madness sooner or later. Anna Vovan‘s work “Gap” shows photographic paper pushed through the narrow gap between door and floor and thus randomly exposed to light on the other side.

The gap is a tear within the fabric of communication: a boundary and opening at the same time. A possibility to communicate despite the barriers. A message pushed through a door gap could also be a letter, a request, a cry for help, a conspiracy, a statement against isolation or incarceration, a chance to overcome the monad of subjectivity. Might “Gap” revolve around forced silence or doors slammed shut? Does it revolve around an affluence or a lack of words? In “Gap” the abstraction of the image questions words as signifiers, but not the act of communication itself.

Maik Schlüter

Photogram

30,2×24 cm

Photogram

30,2×24 cm

Photogram

30,2×24 cm

Photogram

30,2×24 cm

Photogram

30,2×24 cm

Photogram

30,2×24 cm

135 Pigment prints

je 29,7×21 cm

Pigment print

29,7×21 cm

Pigment print

29,7×21 cm

Digital C-print

80×142 cm

Digital C-print

80 × 142 cm

Typewriter on paper

29,7×21 cm

Digital C-print

80×142 cm