Das Innere der Faust

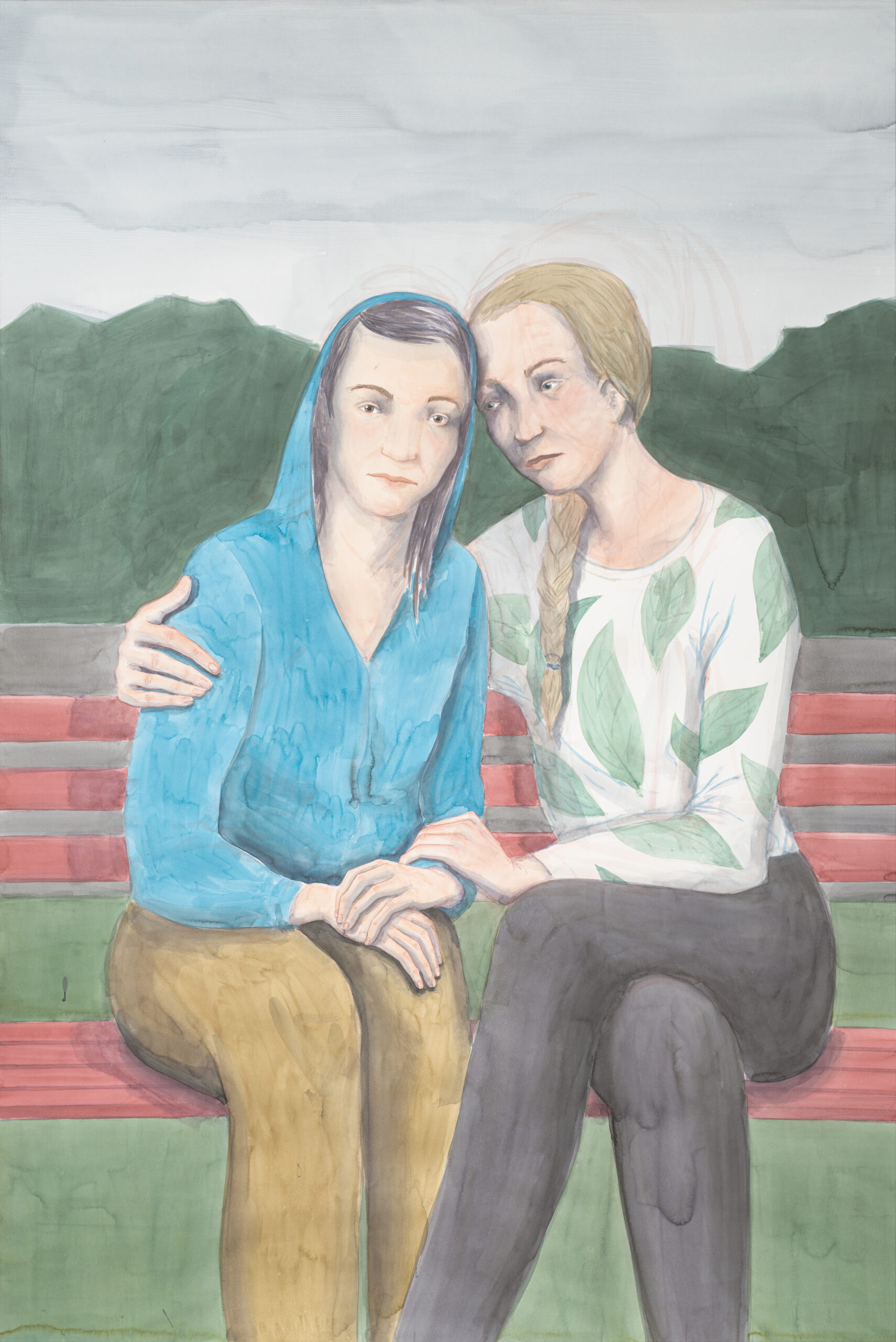

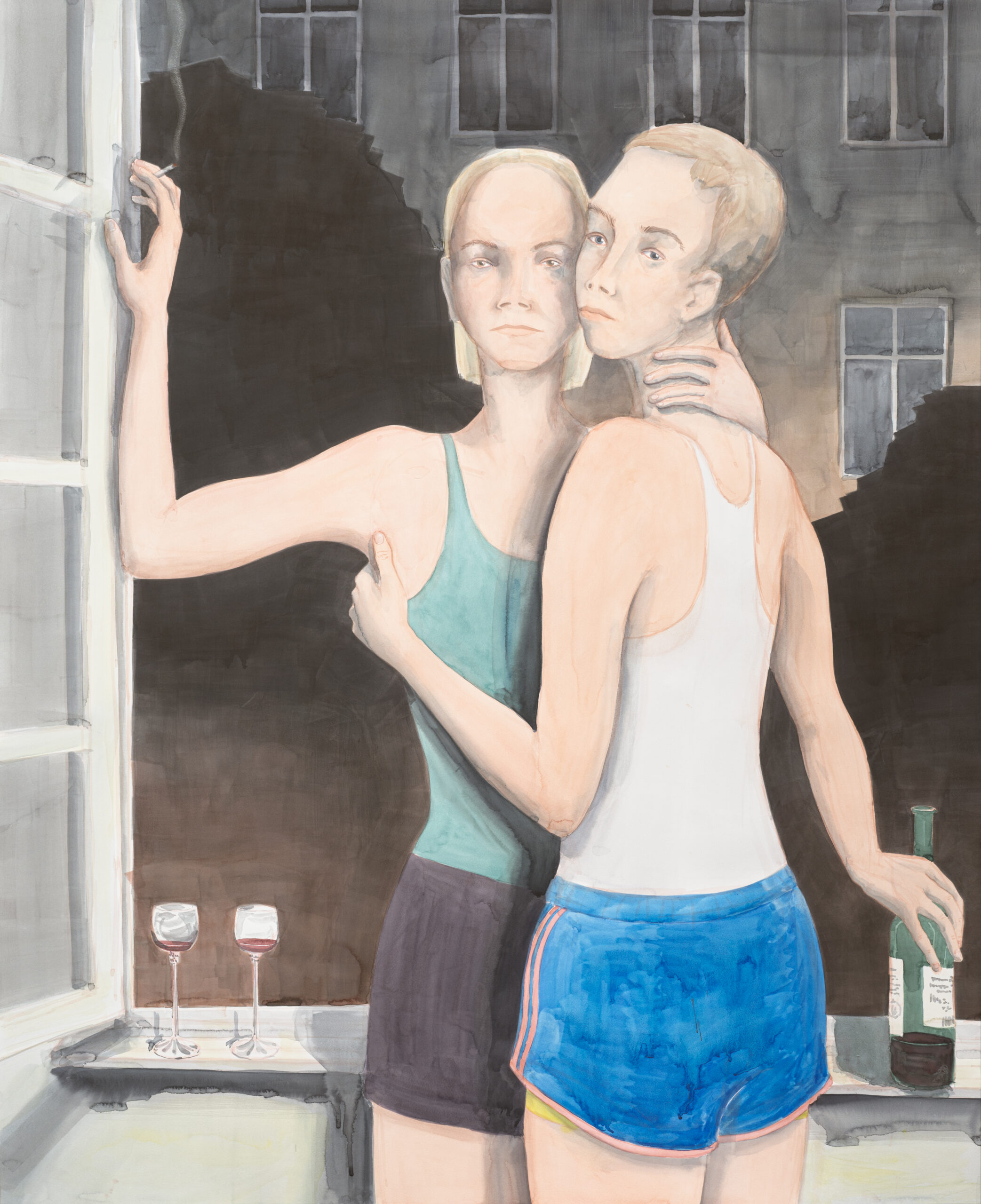

Her motifs are social constellations – not so much the people themselves, whom Anna Kempe’s large-format watercolor paintings depict. Constellations of friends, partnership relationships, parent-child constellations. There is a melancholy that sets in as soon as one person is joined by a second or third. In most cases it is moments of friendship, of conflict, of thoughtful closeness that are given space in the pictures. Our gaze is directed to the mutual care of people who are drawn to each other. Simple family connections give way to kinship of personalities.

With the cancer deaths of both parents, however, Anna Kempe began a more intensive examination of her family history, a retro-

spective on her own development as a person. How is a biography written? Already the key protocol data, recorded in official papers, stamped and stapled, are a narrative that merely sets the framework for the history of a person. In a lifetime, traces accumulate in the most diverse forms. A body acquires scars and drags along a tail of artifacts. Photograph albums condense periods of life into a few pages. How much does the voice, spoken word, have to do with memories?

Hidden Treasures of the Amber Chamber

In the audio installation „Hidden Treasures of the Amber Chamber“ childhood memories are told, family stories are passed on. Grandmothers talk about the post-war period. Moments with deceased parents flash up, life’s last encounters. Heirlooms, their paths and repurposing, displacements of meaning come to the mind. Stories within a family attach themselves to such objects. They accompany an oral tradition that requires new interpretations, translations, and adaptations with each transmission.

The selection of objects, precisely accentuated here, determines the forks along which the story moves, decides on a direction. The tea bowl potted by the mother. A friend’s tiny crocheted airplane. The rings are heirlooms from great-grandmother. The Maxie Wander photograph was found in her father’s estate, who himself is mentioned in Wander’s diaries. The jacket appears in one of Kempe’s paintings as well as in the spoken texts. The amber shard makes it clear how memories wrap themselves around objects. “The Amber Room” is a place of mystery and loss, intimately interwoven with 20th century German history. Baltic amber stones, in turn, are treasures that a GDR child came closest to finding. The sliver captures the place of longing of childhood, the search, the happiness of finding, also the competition between siblings.

Keeping one’s own history in one’s fist

In a fist one protects small treasures from the grasp of robbers or sisters. But one also holds a fly or a grasshopper captive. You can squash it if you want to. Both Anna Kempe’s parents were potters – an artisan’s way of working with ductile material for art and utility objects. The first grasp into the clay makes one familiar with the consistency, one squeezes it out of the fist with the contracted hand – the grasping reflex of an infant and a research movement: experiencing the material with the senses of the skin of the hand. For Kempe, this is an approach to the living world of her parents. The fist, however, is also a symbol for an emotional movement between resistance and rage. The less material fills the remaining gap, the greater the tension.

Collective connections of meaning, especially in a family, between sisters, are created by rituals. If continuity breaks down – e.g., through death or separation – reconstructions are necessary. All the more so between generations, grandparents and grandchildren or absent parents. In contrast to the private spaces in Anna Kempe’s paintings, the exhibition space retains an archival character. Archives are quarries of memory, spaces of analysis, experimental assembly, and storage. One can help oneself from them, rearrange them. In the laboratory, things are also fabricated and examined more closely. The simultaneity of the memory arrangement forces decisions, a selection. This requires work – the premise for retaining power over one’s own narrative.

Marcel Raabe

watercolour on paper

192,2×143 cm,

watercolour on paper

146×201,8 cm

watercolour on paper

143,3×191,2 cm

watercolour on paper

70×100 cm

watercolour on paper

100×70 cm

Die perfekte Zeichnung

On one of our trips to the Baltic Sea, which in my memory never took place in summer, but always at cold, wet, stormy times of the year, I made the perfect drawing. I drew with a stick in the wet sand, a figure, a dwarf, and I knew that I had never made such a good drawing before. It was not the adults‘ confirmation, but I knew myself that everything was right here, the line, the proportions, everything was perfect and at the same time I knew that this drawing would pass away, that I would not be able to keep it or keep it. This was sad, but bearable, because this moment of perfection filled me so much that it had more value than the result.

part of the audio work Hidden Treasures of the Amber Chamber

Neid / Scham / Väter

I’m listening to the radio play adaptation of a performance. Testament – King Lear, She She Pop and their fathers. Here it comes, the envy. I know it already, it catches me when I see a woman my age on the street with a version of herself 20-30 years older. It comes as a sting, as pain, and I have to look away and stare at the same time. Want to observe, want to know everything, want to know how it feels. Am angry that this stranger has something so natural that I will never have. With the fathers I didn’t know that yet. There the closeness is not so obvious, publicly visible. But in the play, it’s there.

There, these children challenge their fathers. To get involved with them and their questions and their art. And these fathers get involved and argue and search and go into the argument. And I’m envious, jealous, but I also wonder if my father could have done that. Whether I could have. And that’s where the shame comes. And I don’t know if my father, who didn’t study and was struck with the male superficiality of this generation, if he could have gone into contact like that? Would I have dared to challenge him like that?

part of the audiowork Hidden Treasures of the Amber Chamber

146,5×116,8 cm

watercolour on paper

146,7×205 cm

watercolour on paper

100×70 cm

watercolour on paper

147,2×96,2 cm

watercolour on paper

147×98,3 cm

watercolour on paper

141,2×189,6 cm

watercolour on paper

134,6×109,8 cm