ANGRIFFSLUST

In the painting „Ausflug“ from 2005 the artist Paule Hammer attacks his own existence. In a garage we see a hybrid of man and monkey sitting on a motorcycle and playing the racer. The contradictory and all too often repressed proximity of monkeys and humans is taken up by Hammer and cleverly caricatured. He himself is the subject of his reflections, for a common social cliché equates male libidinousness, aggressiveness, self-expression and reproduction with the rudimentary actions of the animalistic. The vital struggle for daily survival, raw and existential, has degenerated via evolutionary and social processes to such an extent that not much remains of the male fighter. Life conflicts have shifted and changed, the use of the body and instincts is of only limited help. The man has to channel and compensate his virile impulses: for example, he likes motorcycles or cars, tinkers with them and reinvents his lost potency. In this case, the excursion of the painted motorcycle monkey man ends fatally. At full throttle, the exhaust fumes of the stationary vehicle are inhaled in the locked garage. Hammer shows the staging of a motorized suicide. He dismantles every myth of male activity, liberation and self-determination. A monkey on the grindstone can be seen there, driving his life to the wall without a horizon. The drafts of the artist’s paintings are stuck to the garage wall. The art circus also lives on the myth of the creative man who has access to his primary processes and who manages to bring his emotions onto the canvas in a vital and ingenious way. What sounds like a ridiculous and archaic gesture is unfortunately still part of the self-image of many artists. The dressage imposed on the actors, the expectations that want to be aroused and satisfied, the images and self-images that accompany art and production, roles and functions, are more retrograde, hardened and simple-minded than one would expect. This contradictory agglomeration of masculine energy can be found in many of Paule Hammer’s works. His artistic vocabulary confidently transcends the interpretive offerings of psychoanalysis, anthropology, or sociology. Nevertheless, his self-images reveal a tense relationship to his own person and role. However, he does not address this with therapeutic depth, but rather with aggressiveness, formal precision, and with pictorial and verbal wit. Hammer’s self-portrait in the wall installation „Get Me Out of Here, Mama“ from 2002 is a good example of this. Hammer gives himself a self-deprecating air and shows himself as a milky face with a strong beard, whose melancholy-depressive wish is to finally just want to sleep. If this escape from reality does not succeed, there remains the Oedipal cry for help for the titular Mama, who gets him out of all this madness. The madness consists of the offers that the daily visual garbage washes into the consciousness. Hammer installs the absurd hodgepodge on a faeces-brown background directly on the wall and frames these meaningless trophies and effigies with hubcaps that embody pure simplicity as status symbols.

His art puts the anonymous material in relation to his own experience and turns each thing in the light of his own imagination. Hammer does not collect indiscriminately, but consistently formulates his own artistic fiction and form in the installation. Hammer’s images rarely appear as individual statements. They are usually grouped and arranged in tableaus or extensive installations. He manages to install pictures and to let installations become pictures. The installation „Valhalla“ from 2003 gets to the heart of this formal ability. „Valhalla“ is a roughly carpentered kiosk hung inside with a multitude of images: Mahatma Gandhi, Harald Juhnke, Van Gogh, Roy Black, Che Guevara, Johnny Cash, Jesus, various comic figures, and all the other media characters with their distorted features. In short, the whole repertoire of the culture industry, which manages to equalize and trivialize any political or cultural expression. These masks of entertainment are above all offers of identification. In this media overload, the task is to pick out one’s own pearls and make them stand out. The fact that such a composite identity is shaky, since it consists of fictional and anonymous fragments, is clearly shown by the patched-together installation: a warped shed built from scraps, without any real windows or doors. On the clothesline hang the worn-out garments of the inhabitants: a self-painted jacket, on which various self-portraits of the artist can be found, looks like a helpless attempt to take the matter of self(discovery) into one’s own hands for once, or a bra designed with big eyes on both cups; the applications are just as silly and helpless as their owners. Hammer’s installation is unmetaphorical and does not suggest a metaphysics of feelings and meanings. What there is to see is what there is. Nothing more and nothing less. With his 2005 work „Nobody Knows What We Feel,“ Hammer moves away from exuberant combinations of materials and images. He concentrates on the elaboration and presentation of a sculptural figure on a large scale. A head sculpted from papier-mâché and other materials depicts Klaus Kinski. Kinski’s biography and artistic career is more than contradictory. Known as an impressive reciter of world literature, in the sixties he could also be seen as an infantile lunatic in bad BMovies, before he repeatedly drew attention to himself through scandals with renowned directors of the European avant-garde. Not least with his autobiographical notes, full of sex fantasies, cynical utterances, but also captivating with poetry and analytical thoughts, he eluded clear categorization. Like no other, he mastered „the acrobatics of identification, the art of getting in,“ as was read on the anniversary of his death. Hammer does not erect a monument to the artist. His sculpture is more a continuation of Kinski by other means and a brilliant quote on the artist’s „waterhead existence.“ A huge skull that can think and represent everything and yet sits like a puppet on a thin neck. A hollowed out character actor, overdrawn and stretched. Size, colorfulness, the whole expression of the work express this in a grotesque way. The imbalance between the possible and the actual, between staged and real madness, cannot be satisfactorily resolved. And there are no simple answers either. „No One Knows Any More“ is the title of a novel by Rolf Dieter Brinkmann, and this title is not far from what Paule Hammer says. His paintings and tableaus do not show the popular subjects of contemporary painting: space, architecture, and the supposed fourth dimension of surreal wonder and parallax displacement. And when Hammer does make use of these elements, it is under the auspices of destroying meaning-warping and self-congratulatory abstraction. In Hammer’s paintings there is a conflicting play with the levels of meaning in painting and the psychology of the artist. At the same time, he creates a palpable and open plane of pathos and melancholy that concretizes his existential themes. He does this without dogmas and didactics, changeable and exciting in his forms of expression; from installation to canvas to paper to waste sculpture to poster art. Paule Hammer’s works are smart, precise, abysmal and oblique like the works of Mike Kelley and thus less obtrusive and striking than the material and word excesses of a Jonathan Meese.

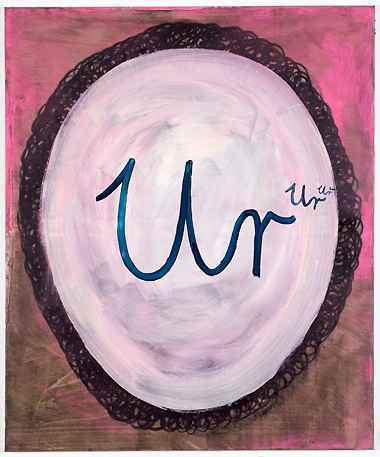

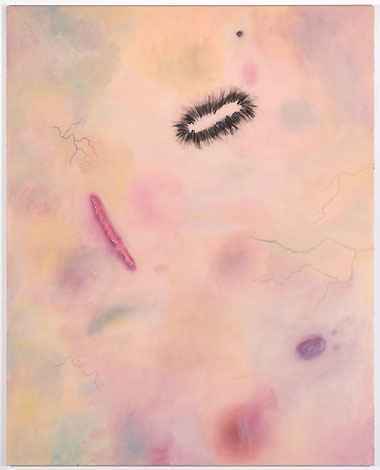

„Hit Him If You Can,“ the title of one of Hammer’s exhibitions, perhaps expresses his delight in provocation, but narrows the discussion too much to masculine confusion. Much more important, on the other hand, seems to be his ability to speak a wide variety of visual languages: Dismantling of art myths in gloomy comic style, self-irony and launched naivety is presented on the canvas with strong color application, writing appears as a grotesque commentary in skillful poster-painter gesture, spatial views and landscape details are precisely painted, and his sculptures and installations show spatial and material understanding. Forms and fictions of his own art are constantly juxtaposed and judged differently. This restlessness and aggressiveness express Hammer’s productive conflict: the artist against himself, art against reality and against the reality of art. Nothing stands for itself, everything is in conflict, does not fit together, and opposes any desire for quiet agreement.

Maik Schlüter, VG Wort Bonn, 2006