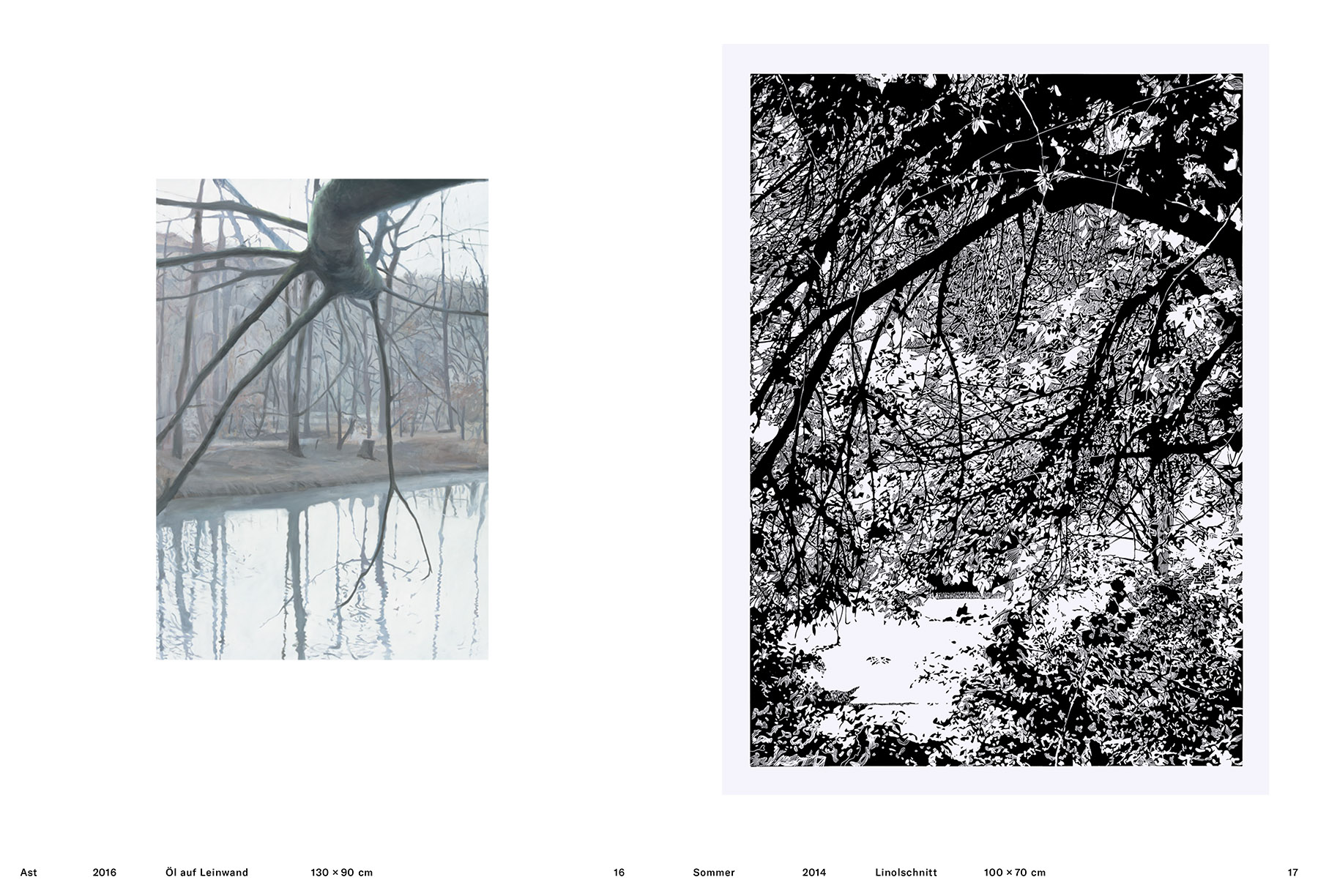

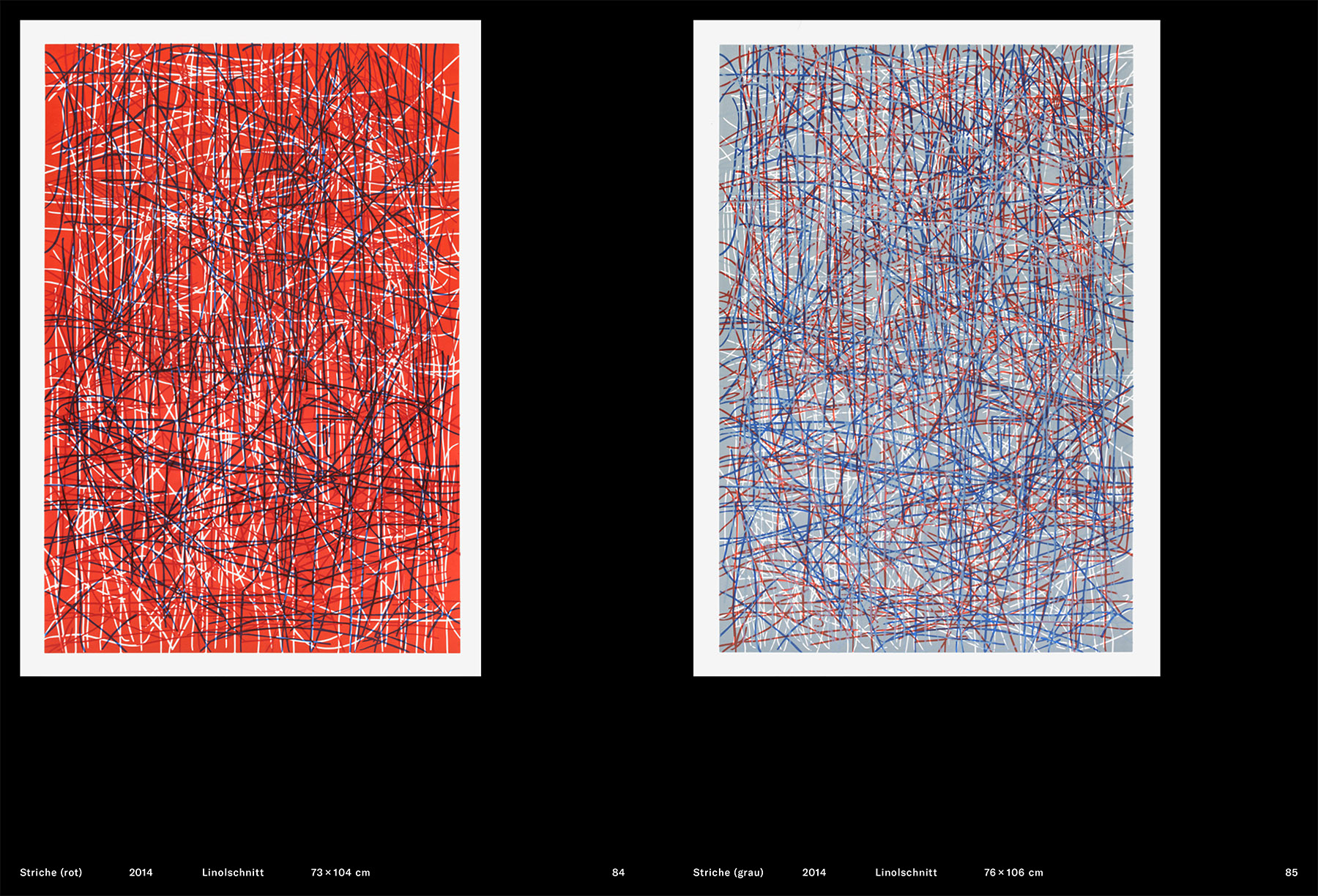

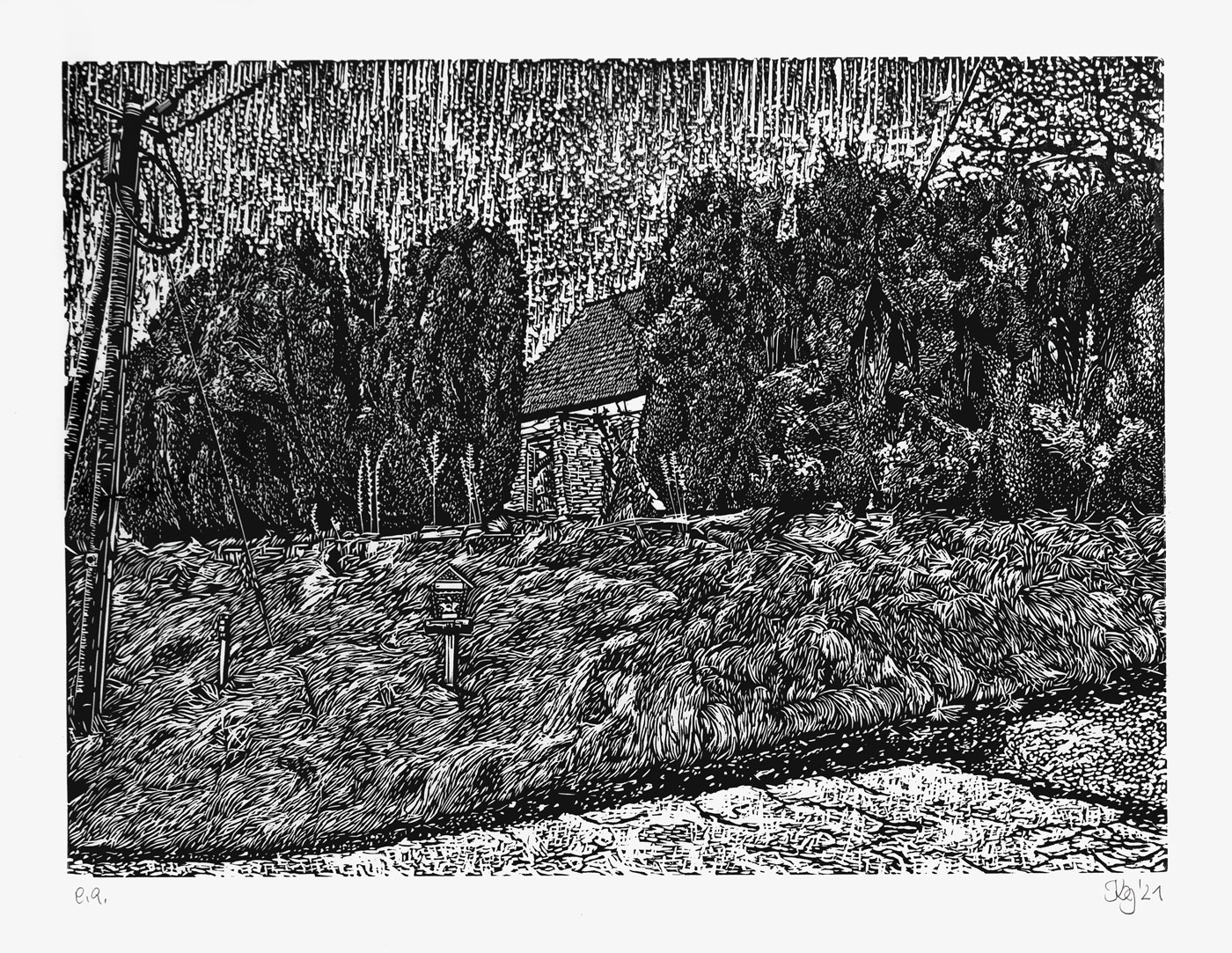

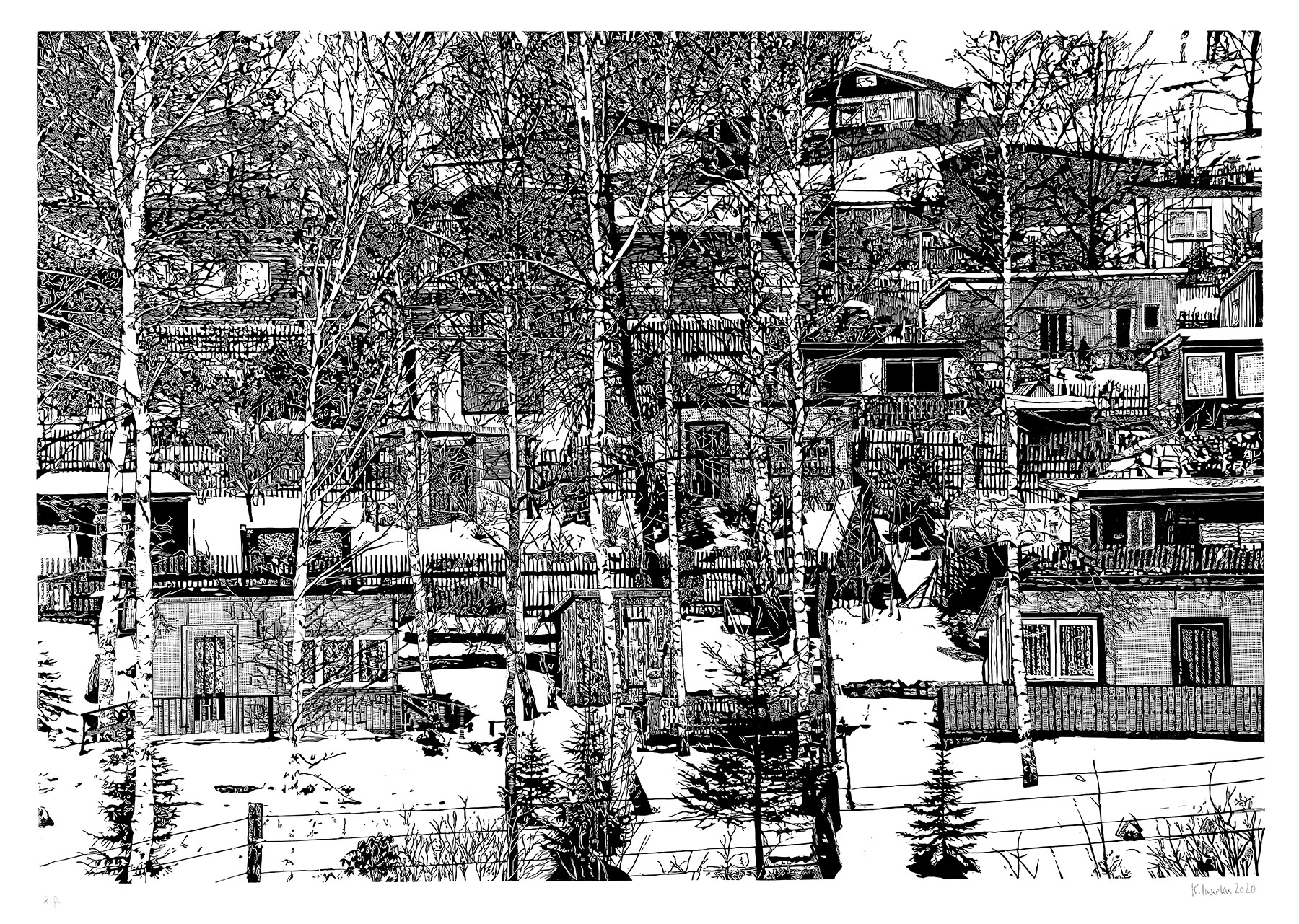

The sparse trees act like a perception filter. Houses spread out behind them. They are visible because it is winter and the birch trees have no leaves. Kleingartenbungalows or pavilions, Vorgartenmäuerchen and parking bollards, also new buildings in a historical urban setting. Lanterns, fences, corrugated iron roofs. The realistic depiction in Katharina Immekus‘ linocuts initially focuses on detailed objects. But what is most important is their relationship, their respective position: between two spheres, in a transit area where a translation must take place.

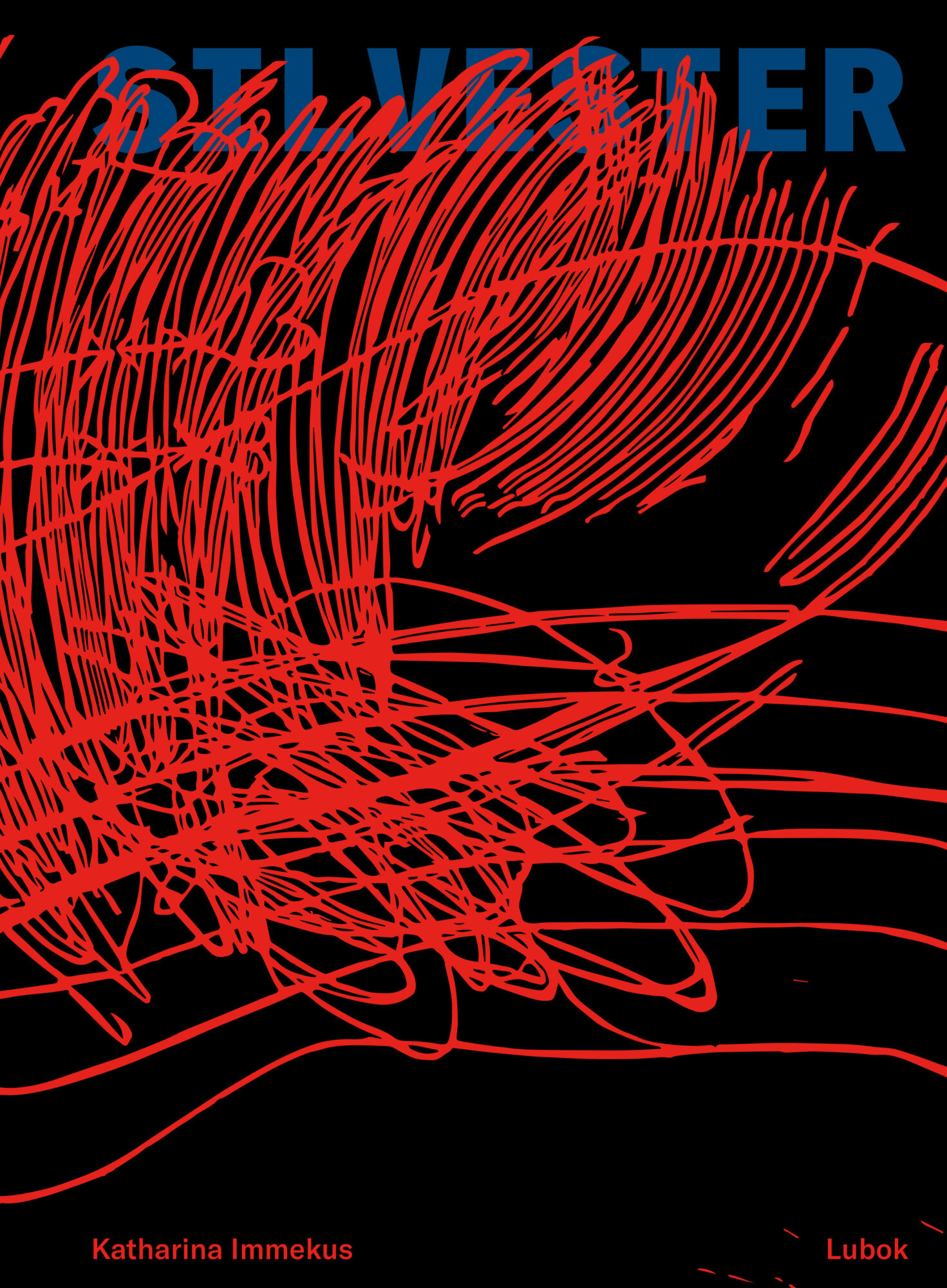

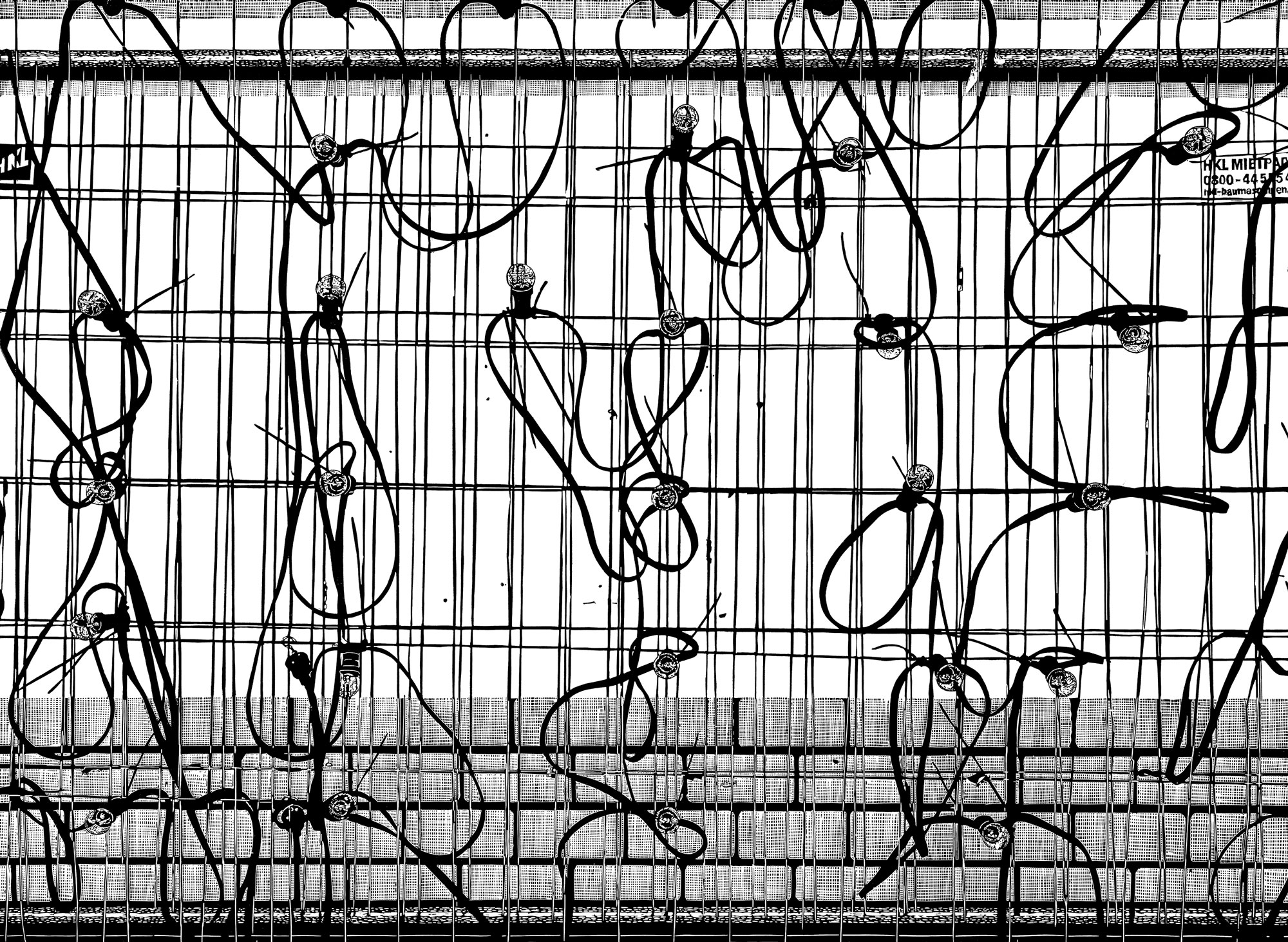

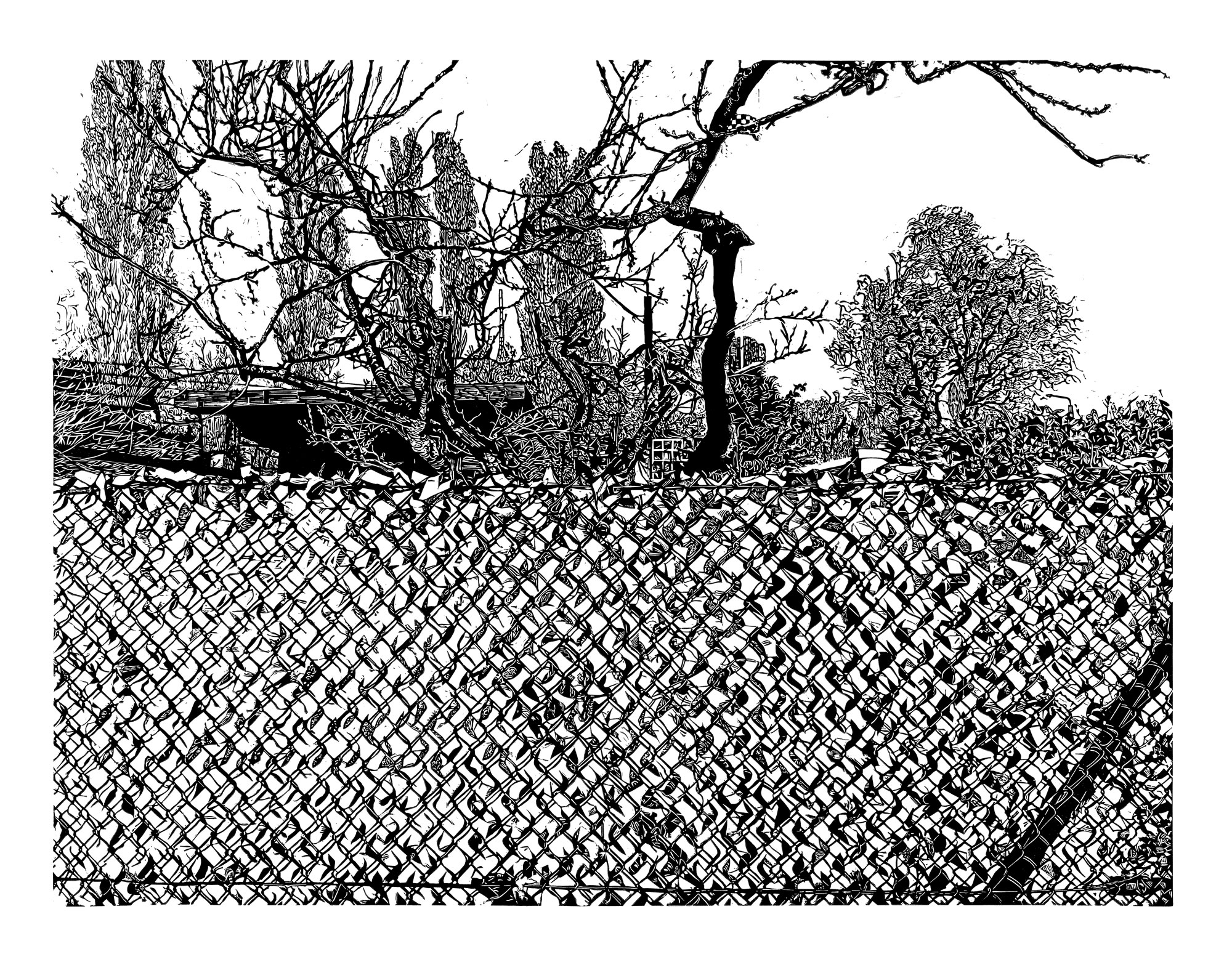

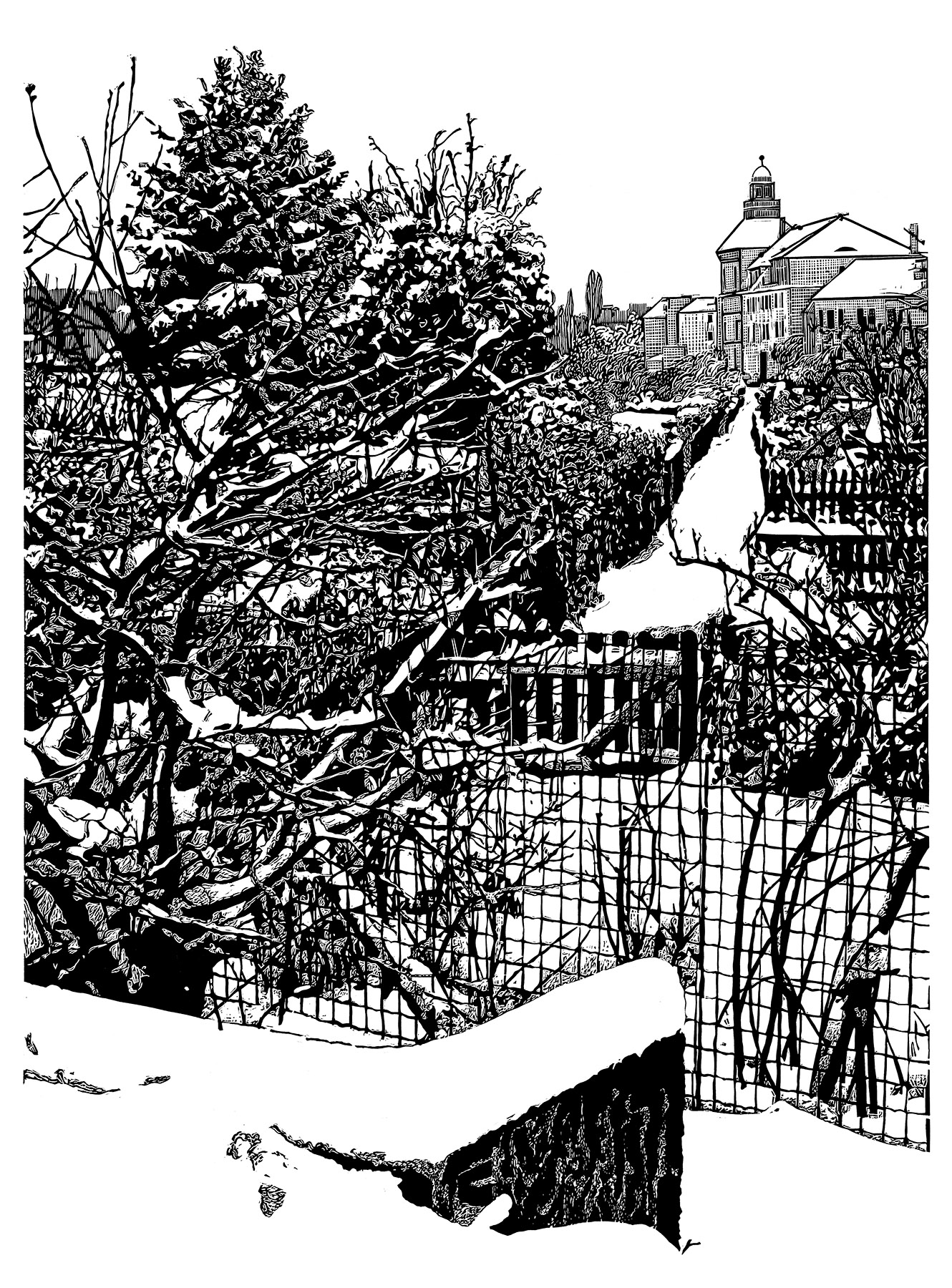

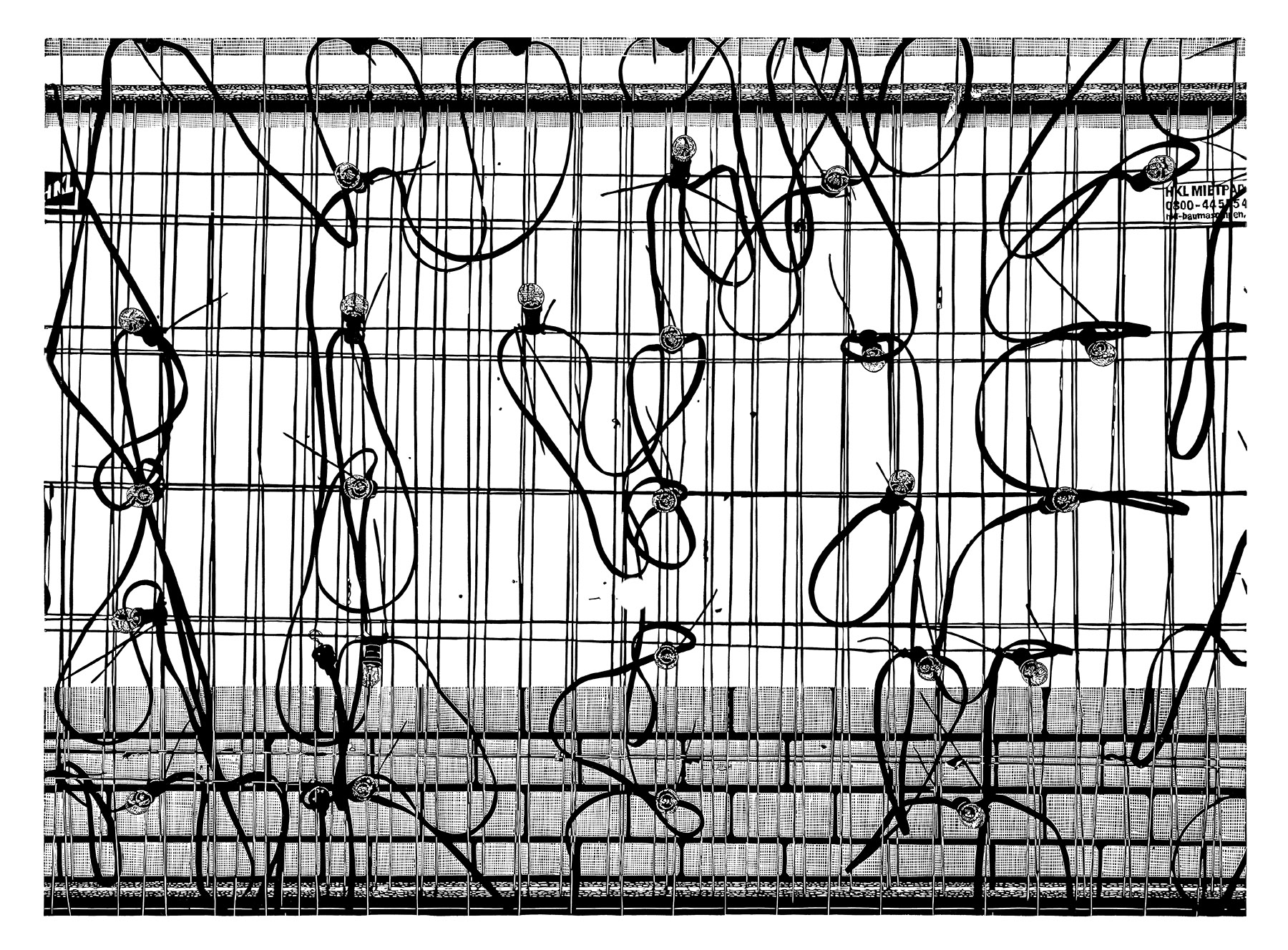

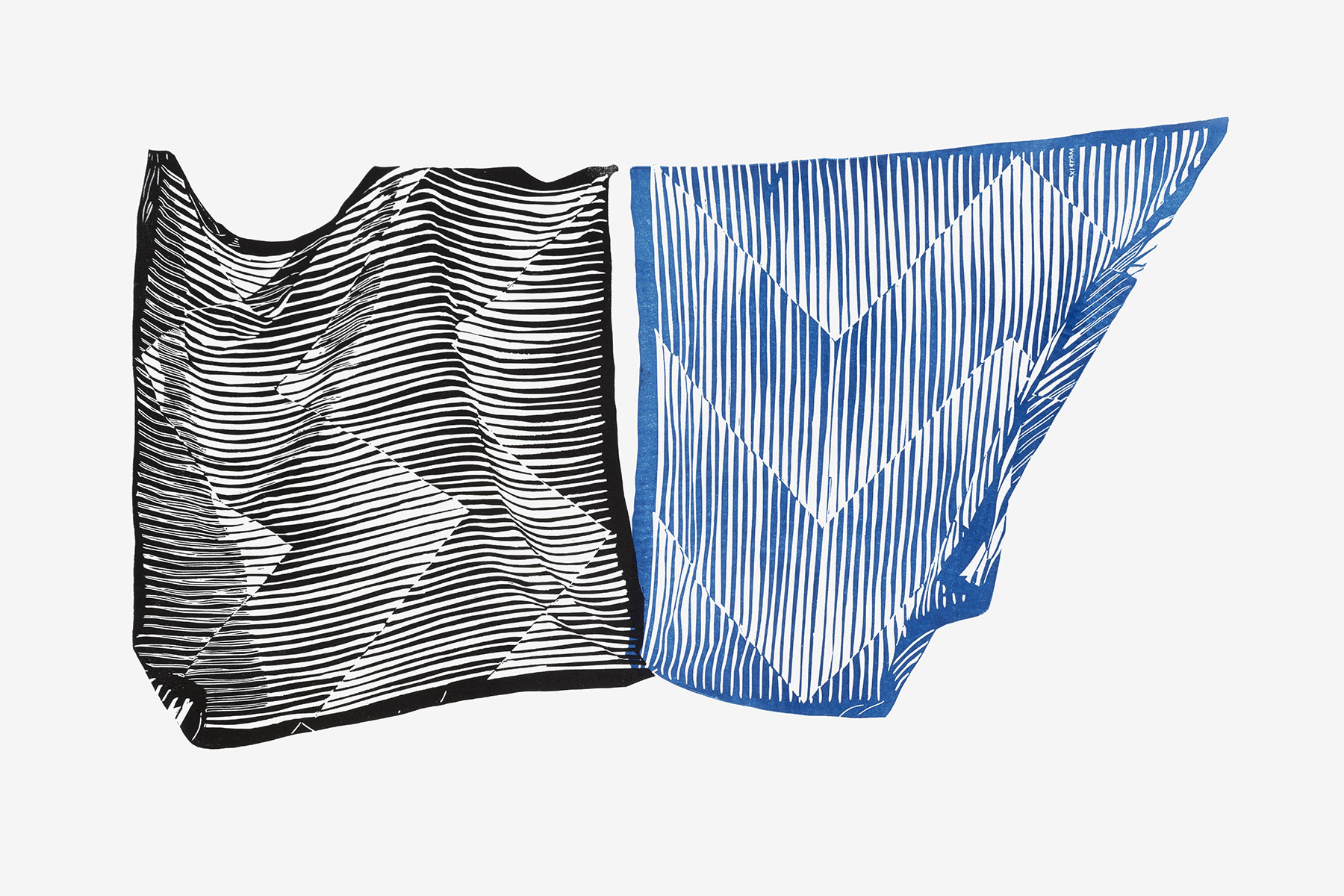

The pictures themselves reject mediation; it is not their primary interest. Rather, it is the space in which this process takes place. It is not a matter of spectacular transformation landscapes, ruinous monuments of decay or violent human intrusion into supposed natural idylls, as in the reconstruction pictures of Socialist Realism. In Katharina Immekus‘ work, on the other hand, one can wander through the unagitated, everyday inventory of the marginal areas; temporary architectures, allotment plots, desolately cut bushes. Even the numerous fences depicted give an indication on the nature of these transitions, which are also historical transitions; along board fences over wire nettings, to contemporary construction grids. They are the indication that time structures in these border zones are different. There is a spatial before and behind, like a temporal before and after on New Year’s Eve. The time-consuming, intensely crafted linocuts stretch the snapshot-like moment of Sunday rest to the extreme: the exhibition title „Silvester“ refers to the day when the artist spent hours transferring the sky onto a linocut of the same name.

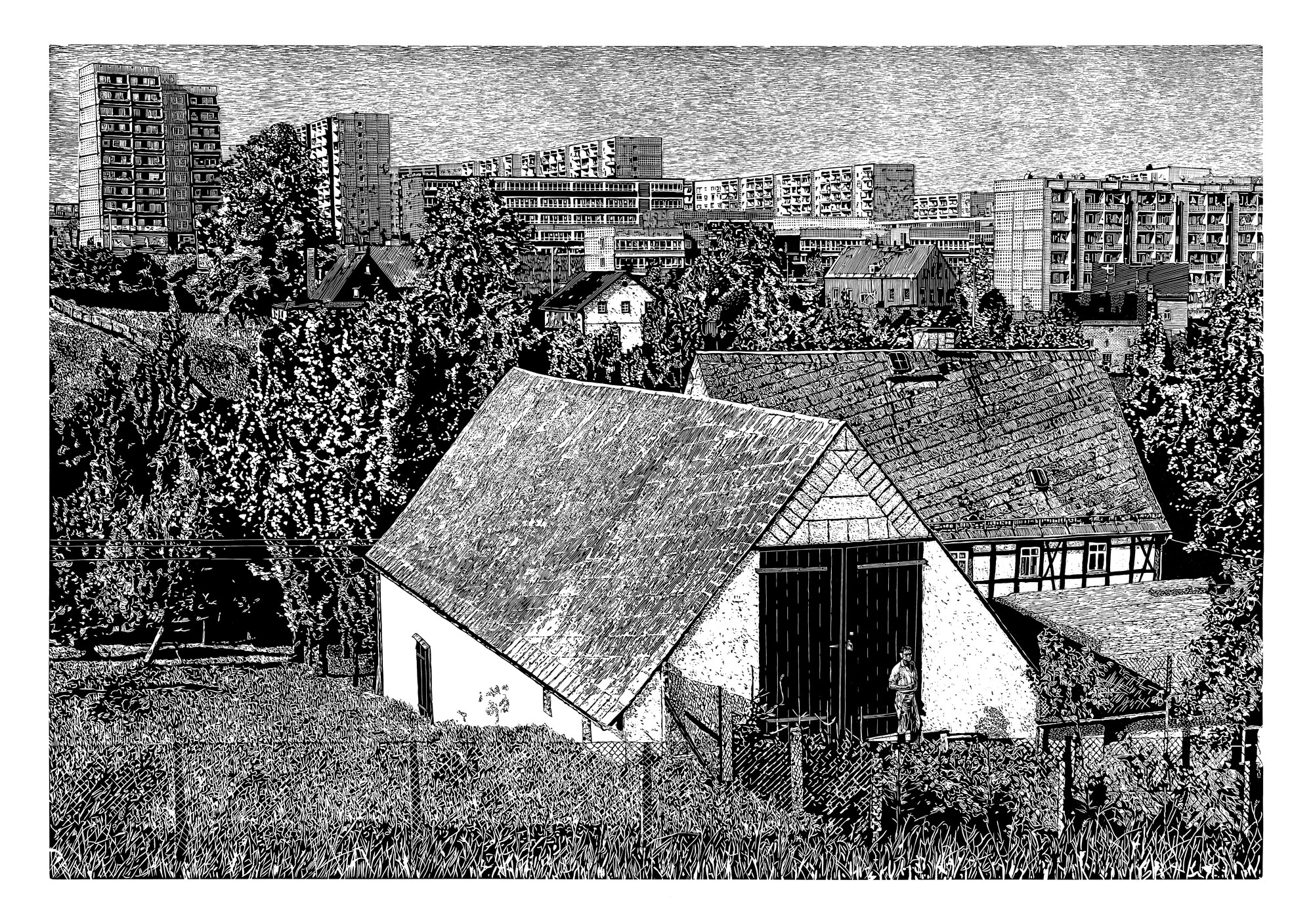

Yet boundaries are not always so clearly drawn as with a fence. A hedge can be similarly insurmountable. By pretending to be nature, it distracts from the demarcation, and even blurs the border. And when, as in the picture „Silvester“, the prefabricated housing estate and the half-timbered village almost grow into each other, it seems spatially dissolved. But of course the break is clearly visible: between old and new, tree and concrete, the individual and the many. The peripheries are not wilderness; nature and culture are not opposites, but in the border regions in which the artist moves, they relate to each other, belong to each other. The allotment garden would be inconceivable without the city, as the city without a reference to what it is not: unbridled nature. It is at the margins that differences become negotiable, compromises are made, the eye turns blind and differences are established in the first place. The margins make work, even if they promise relaxation. Katharina Immekus sends postcards from there.

Marcel Raabe, 2021

Linolschnitt

80,5×103 cm, 10+1 AP, 2020

Linolschnitt

96×134 cm, 5+1 AP, 2021

Linolschnitt

50×64 cm, 10+1 AP, 2018

Linolschnitt

84×64 cm, 10+1 AP, 2020

Linolschnitt

38x48cm, 10+1 AP, 2021

Linolschnitt

100×140 cm, 10+1 AP, 2020

Linolschnitt

71×89 cm, 10+1 AP, 2021

Linolschnitt

78×108 cm, 10+1 AP, 2020

Öl auf Leinwand

70×50 cm, 2019

Öl auf Leinwand

70×100 cm, 2019

Öl auf Leinwand

82×100 cm, 2019

Linolschnitt

40×50 cm, 2019