Local Field

The surreal beauty of a chard leaf. Where does it come from? For one thing, it lies in the contrastingly prominent veining of this leaf. The ramifications stand out because of the flash. They acquire significance because the leaf receives an attention in the close-up that it would not have as a simple meal. Above all, however, it reveals itself in the coloration, which is perceived as unreal.

Verena Winkelmann’s interest in the food plants arose from the movement. The contemplative encounter with „nature“ is ambivalent, however, because the cultural landscape she has been roaming since 2018 is processed space: cultivated fields are industrial production sites in which the individual specimen of a plant is initially irrelevant. This is contrasted by efforts to achieve ecologically sustainable agriculture. Here, more attention is paid to the individual plant, which is much more exposed to environmental influences without chemical aids.

In large-scale enterprises, aesthetic issues become relevant only in the context of presentation, advertising, and commercial norms. Winkelmann’s observations on a small ecological farm turn the aesthetic aspect into an artistic perspective. In this, respect for agricultural work done by hand is expressed. The images of food in its raw, unprocessed form are the result of a search movement beneath the (earth’s) surface.

VW 1998/2000

Verena Winkelmann directs this gaze at herself in the series VW 1998/2000. From a distance of more than 20 years, the portrait series not only documents a phase of finding a female identity. By experimenting with the conventions of representation of „femininity,“ it also records how the artist once discovered photography for herself – in the sense of a technical apparatus as well as an attempt to stage her own person. Because they are self-portraits, she has control over the image, unlike professional models. However, because the representations of women in the medium of photography – be it fashion, vacation, or erotic photography – are predetermined by well-rehearsed image routines, this autonomy is deceptive. Today, in contrast to changed photographic techniques and the self-staging in social media, the series offers the possibility of a media-historical reflection.

Lunch in Norwegian

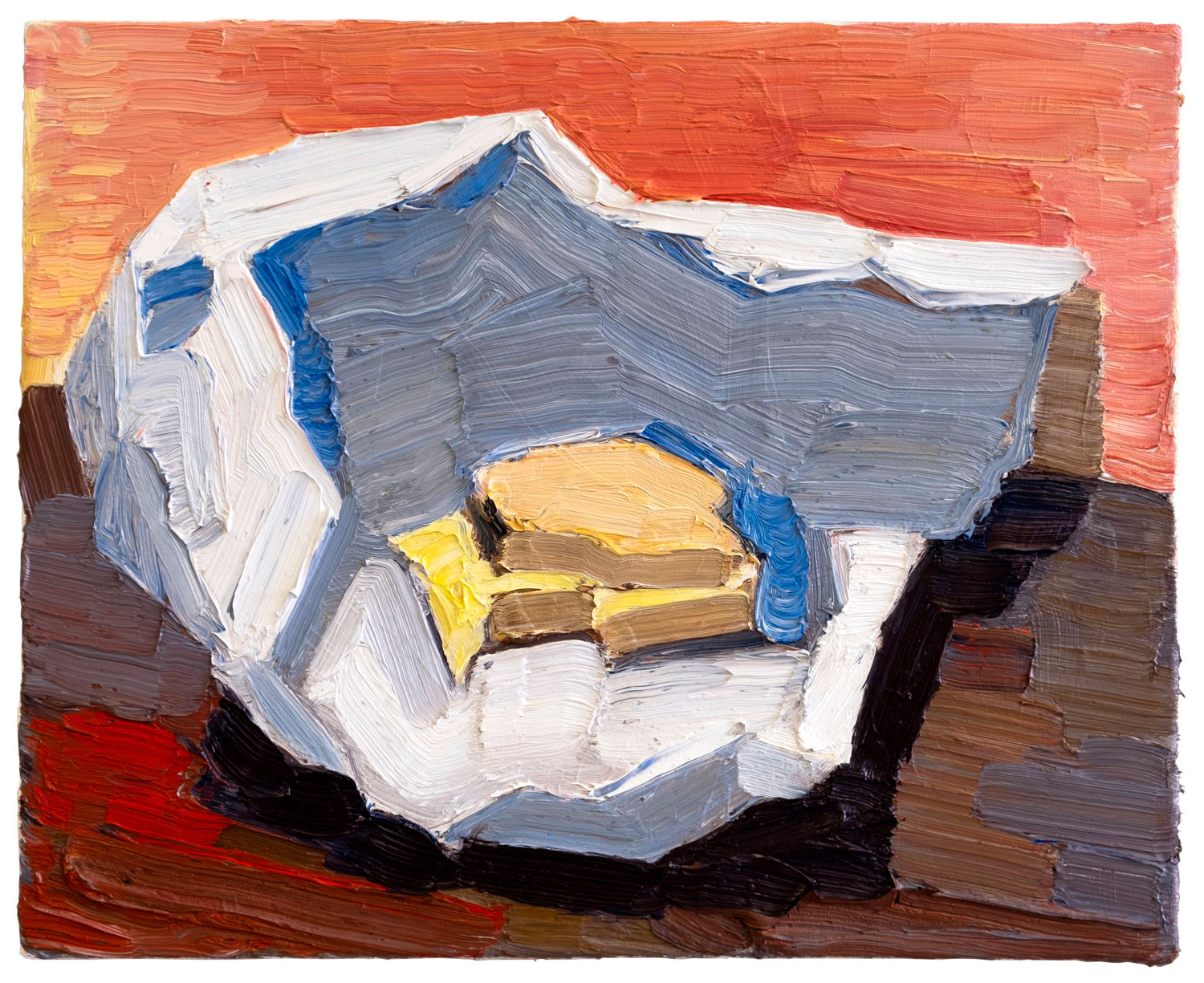

Aleksi Wildhagen adopts a similarly exploratory perspective with his paintings. Here, too, the motifs appear as the medium of a process. It is about the artist’s confrontation with his immediate surroundings, a narrowly defined circle of perception that encompasses the person. The fact that eyeglasses, ashtrays, or sandwiches are depicted is initially secondary for Wildhagen. But in the act of painting the things that are depicted give rise to an alternative, private interspace that opens up access to existential questions of being for both the artist and the viewer.

In the same way, the numerous self-portraits become the starting point for an examination of the current situation in life. In them, a moment of insecurity is expressed: „Recently I felt like my body and mind are positioned at ground zero,“ says Aleksi Wildhagen, „both because I am a white male, which has reached a certain boring age according to the general opinion, but maybe foremost because I have a kidney disease and I’m waiting to get a donor organ.“

The view of oneself intensifies as one’s own body is perceived as precarious, as positions that were thought secure begin to falter. Reflection on a natural environment – whether through walks during a pandemic, in the wake of illness, or approaching wars – is often done consciously or unconsciously under the impression of a threat. The access of something whose control one cannot gain always means: limited resources, new limits, learning to deal with what one has at one’s disposal.

Self-empowerments

In the self-portraits, the work complexes of Winkelmann and Wildhagen, very different in their form, touch each other. Both contrast the contemporary frame of the „selfie“ in their own way. While in Wildhagen’s painting the aspect of duration is a counterpart to the quick smartphone snapshot, the difference in Winkelmann’s pictorial situations, which are also very carefully constructed, is established by the age of the series: when it was created almost 25 years ago, self-staging on social media platforms was not yet common knowledge.

The artistic use of the forms of painting as well as photography, the analog image creation as a counter-design to today’s digital everyday practice, are an active rewriting, an attempt to gain control, to assert autonomy. In this respect, both Verena’s and Aleksi’s works are documents of self-empowerment.